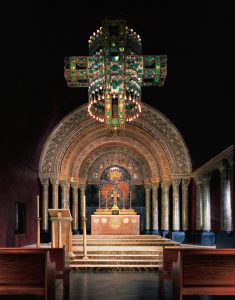

Although created by Tiffany’s newly founded firm, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, to demonstrate its artistry and craftsmanship in producing ecclesiastical goods ranging from clerical vestments and furnishings to mosaics and leaded-glass windows, the chapel, it was reported at the time, so moved visitors that men doffed their hats in response.

Its rich, Byzantine-inspired interior was built up from simple classical forms, columns, and arches, which were huge in size relative to the chapel’s intimate space (1,082 square feet, including the baptistery). Visitors entered another world of intricate, reflective glass mosaic surfaces and light filtered through the intense colors of stained-glass windows—a world that enveloped them and at the same time dwarfed them through its massive architectural forms.

It included six ornately carved plaster arches, 16 mosaic columns, a 1,000-pound, 10-by-8-foot electrified chandelier, or “electrolier,’’ in the shape of a cross, a marble and white glass mosaic altar, a dome-shaped baptismal font, and several windows.

From Chicago to New York

After the Tiffany Chapel won many medals, including one for imaginative adaptation of the electrification of its imposing chandelier, it was dismantled at the closing of the world’s fair.

In 1898, a wealthy woman—Mrs. Celia Whipple Wallace—bought the chapel for the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine under construction at the time in New York City. Never placed as it was intended, the chapel was relegated to a basement crypt where its arches were cut to fit under a low, broadly vaulted ceiling. For more than 10 years (1899–1911) it functioned as a chapel at St. John the Divine and then was closed when the choir above was completed for services.

Unchecked water damage took its toll on the architecture and decoration of the chapel, and in 1916 Louis Comfort Tiffany wrote to the church of his concern that “the mosaic work has suffered” and offered to remove it at his expense.

Reinstalled at Laurelton Hall

Tiffany had the chapel removed and installed it, with substantial repairs by his workmen, in a free-standing building at Laurelton Hall, his Long Island country estate. There it remained as a monument to his art until 1949, 16 years after Tiffany’s death, when the Tiffany Foundation began dismantling the chapel, selling off portions to institutions in the region.

In 1957, when Tiffany’s abandoned estate was ravaged by fire, Hugh and Jeannette McKean of Winter Park, Florida, were notified by a Tiffany daughter that some of his most important leaded-glass windows were still intact. In 1930, after his graduation from Rollins College, Hugh McKean had been one of the young artists in residence at Laurelton Hall as part of a program established by Tiffany. Years later in 1942, Jeannette McKean had established a gallery-now The Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of American Art-on the Rollins College campus and named it to honor her grandfather. Her interest in Tiffany glass had prompted her to curate a show of his work at the gallery in 1955, one of the first one-man exhibitions of Tiffany work in the second half of 20th century.

Rescued to Winter Park

The McKeans visited the devastated Laurelton Hall site, and Jeannette decided they should buy all of the mansion’s then-unwanted windows and architectural fragments. Two years later the McKeans purchased the components of the chapel that remained at Laurelton Hall.

For decades, many of the chapel elements had remained in packing crates as the McKeans researched the locations of the various chapel furnishings that had been dispersed after 1949. They systematically acquired these furnishings as they became available to keep all of the chapel parts in a single collection.

In 1996, the Board of Trustees of the Charles Hosmer Morse Foundation endorsed an expansion project for the Morse Museum that would fulfill the dream of the McKeans to reassemble Tiffany’s 1893 chapel. A team of architecture, art, and conservation experts was named to begin the over two-year project of reassembling the chapel. The chapel opened to the public in April 1999, the first time since it was open at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.